Britain is facing a crisis of child poverty that has been largely ignored by the government and the media. Hundreds of thousands of children are living in homes without basic necessities such as food, heating, and beds. Their suffering is worsening by the day, as the welfare state that was supposed to provide a safety net for them has been systematically dismantled and eroded.

This is the message of a new report published this week by the Multibank, a network of food banks and charities that have become the last resort for many families on the brink of destitution. The report reveals that the number of children relying on emergency food parcels has increased by 50% since the start of the pandemic, and that one in five households with children have experienced food insecurity in the past six months.

The report also exposes the shocking conditions that some children have to endure, such as sleeping on the floor, sharing a bed with siblings or parents, or going without warm clothing or shoes. These are not isolated cases, but the result of a systemic failure of the welfare state to keep up with the rising costs of living and the impact of the pandemic on low-income families.

The holes in the safety net

The main culprit for the worsening situation of child poverty is the universal credit system, which was introduced in 2013 as a way to simplify and streamline the benefits system. However, the system has been plagued by delays, errors, sanctions, and cuts that have left many claimants worse off than before.

One of the most controversial aspects of universal credit is the benefit cap, which limits the total amount of benefits that a household can receive, regardless of their circumstances or needs. The cap affects around 200,000 households, most of which have children, and can result in losses of up to £250 a month. The cap has been widely criticised by charities, experts, and even the UN as a violation of human rights and a driver of poverty and homelessness.

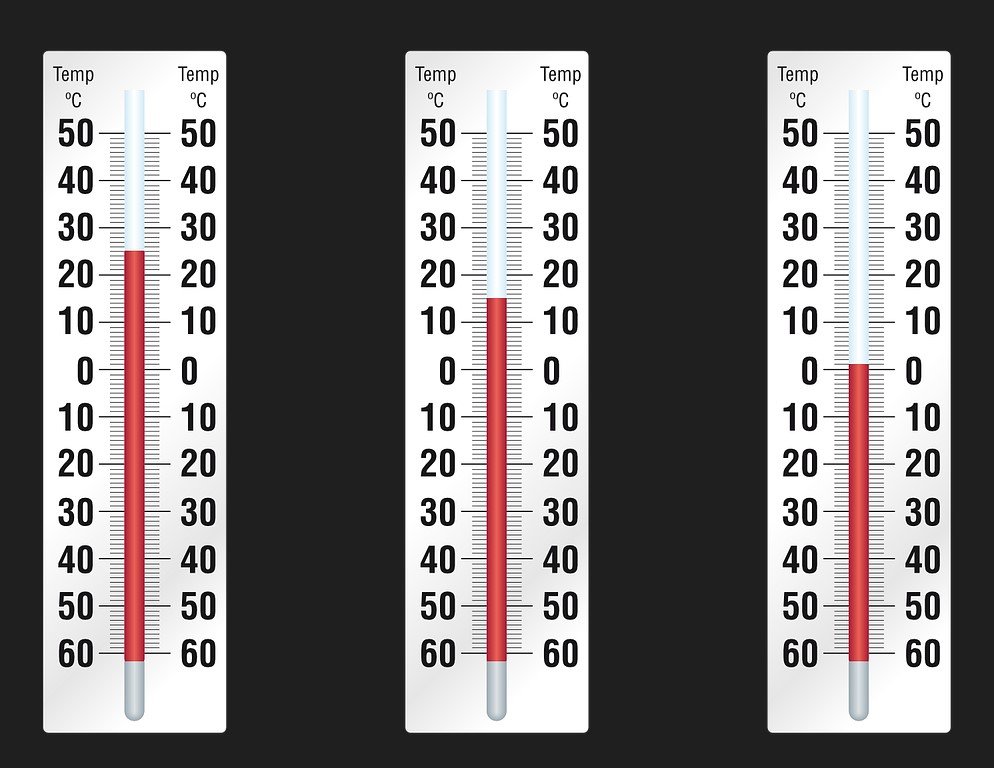

Another problem with universal credit is the inadequate level of the standard allowance, which is the basic amount that claimants receive before any additional elements are added. The standard allowance has not kept pace with inflation or average earnings, and is now at its lowest ever level as a proportion of median income. According to a recent report by the abrdn Financial Fairness Trust, the cost of food and heating alone would exceed the standard allowance for a single person, forcing them to cut back on other essentials or go into debt.

The government did increase the standard allowance by £20 a week in April 2020 as a temporary measure to help cope with the pandemic, but this uplift is due to end in April 2024, despite widespread calls to make it permanent or even increase it further. The removal of the uplift will push an estimated 700,000 people, including 300,000 children, into poverty, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

The need for action and solidarity

The Multibank report calls on the government to take urgent action to address the crisis of child poverty and to restore the dignity and security of the poorest families. Some of the recommendations include:

- Making the £20 uplift to universal credit permanent and extending it to legacy benefits

- Lifting the benefit cap and increasing the child element of universal credit

- Investing in affordable and social housing and ending the use of temporary accommodation

- Providing free school meals to all children from low-income families, including during holidays

- Increasing the funding and availability of local welfare assistance schemes

- Supporting the work of food banks and charities through grants and partnerships

The report also urges the public to show solidarity and compassion for their fellow citizens who are struggling to make ends meet. The report suggests some ways that people can help, such as:

- Donating food, money, or time to their local food bank or charity

- Signing petitions and campaigns to end child poverty and hunger

- Writing to their MP or local council to demand action and accountability

- Raising awareness and challenging stigma and stereotypes about poverty

- Offering practical and emotional support to friends, neighbours, or relatives who are in need

The report concludes by saying that child poverty is not inevitable, but a choice that can be changed by political will and collective action. It says that Britain has a moral duty and a social responsibility to ensure that no child goes hungry or cold, and that every child has a chance to thrive and fulfil their potential.