Innovation in ophthalmology often arises from unexpected places, typically through collaboration between researchers and clinicians. Two pioneering corneal specialists share how their groundbreaking work came to life and what it truly means to be a clinician scientist.

Early in his career, Dr. Edward J. Holland dealt with high-risk corneal transplant patients who experienced graft rejections—sometimes multiple times. “We didn’t fully grasp why these transplants were failing,” he admitted. Determined to find answers, he focused on patients with limbal stem cell deficiency, uncovering layers of clinical problems needing solutions.

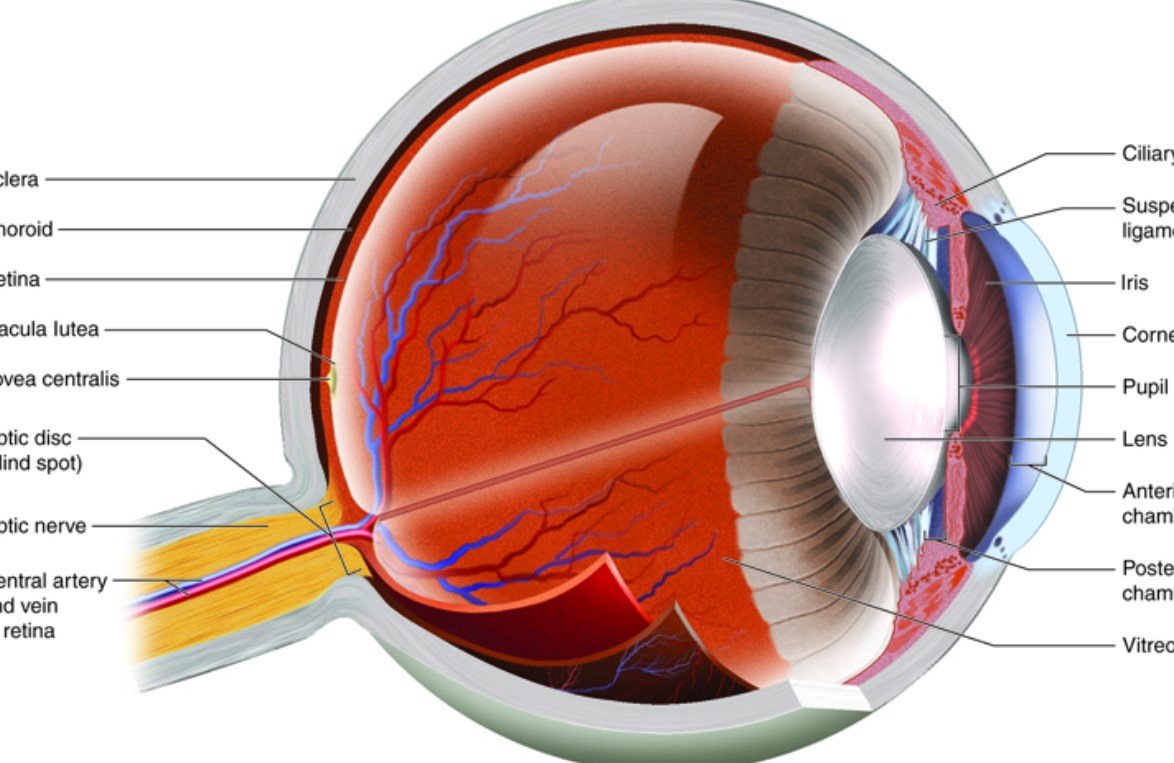

As he explored further, Dr. Holland delved into the role of the limbus and the regeneration of the corneal epithelium. “I kept uncovering new aspects of a clinical problem that I had to try to solve,” he said. This pursuit led him into the field of ocular surface stem cell transplantation, aiming to restore vision for patients with severe ocular surface diseases.

His perseverance highlights how innovation often stems from seeking solutions to unsolved problems. “The seed of innovation is usually failure,” he emphasized. By confronting these challenges head-on, he paved the way for new treatments that have significantly improved patient outcomes.

The Evolution of Novel Ideas

For Professor Shigeru Kinoshita, innovation is less about sudden inspiration and more about relentless experimentation and collaboration. “Turning an innovative idea into a viable medical treatment doesn’t happen overnight,” he pointed out.

Throughout his career, he worked closely with researchers like Dr. Nancy Joyce and Dr. Eunduck Kay, pioneers in cultivating corneal endothelial cells in the lab—a task once considered impossible. Their collaborative efforts at Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine led to successfully reproducing corneal endothelial cells on a collagen substrate. This was a crucial step toward developing cultured human corneal endothelial cells (CECs).

“Even when an idea seems brand new, it has probably taken years of experiments to refine,” Professor Kinoshita noted. He stressed the importance of determination, acknowledging that failures are inevitable along the way.

“Relentless determination is key because there are always setbacks,” he said.

Collaboration: The Key to Overcoming Barriers

Professor Kinoshita believes that listening and engaging in open discussions are vital for success. “The ability to listen carefully and discuss problems collaboratively is critical,” he remarked. Collaborating with mentors, peers, and even students can lead to breakthroughs that might not occur in isolation.

Dr. Holland experienced a turning point when he performed cataract surgery on the wife of Dr. John Najarian, a leading figure in organ transplantation. When Dr. Najarian learned about the issues with graft rejections, he immediately identified the problem: insufficient systemic immunosuppression.

“That was a lightbulb moment for me,” Dr. Holland recalled. Traditionally, ophthalmologists avoid systemic medications due to potential side effects, but adopting organ transplant principles significantly improved graft survival rates.

He realized that applying higher levels of immunosuppression, similar to those used in kidney, liver, and heart transplants, was necessary for the vascularized ocular surface. This interdisciplinary insight was pivotal in developing what is now known as the Cincinnati Protocol for patients with limbal stem cell deficiency.

- Cross-disciplinary collaboration can lead to groundbreaking solutions.

- Listening to insights from outside one’s field can be transformative.

- Persistence in the face of challenges is essential.

Tackling Logistical Challenges

Implementing new treatments isn’t just about scientific breakthroughs; logistical hurdles can be equally daunting.

Dr. Holland needed to hire a transplant coordinator to manage lab tests, medical appointments, and monitor side effects—services not covered by typical reimbursement models. “We had to figure out how to fund these essential services,” he explained.

Coordinating a multidisciplinary team was also essential. This involved retina specialists, glaucoma experts, oculoplastic surgeons, and transplant nephrologists. “Even if you teach a cornea specialist how to do the procedure, coordinating this whole team can be overwhelming,” he noted.

Logistical Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Solution |

|---|---|

| Funding for transplant coordinator | Secured alternative funding sources |

| Coordinating multidisciplinary team | Established collaborative protocols |

| Managing patient follow-up care | Developed comprehensive care plans |

Similarly, Professor Kinoshita understood that culturing endothelial cells was only part of the solution. “Creating cells could help address the chronic undersupply of corneal tissue, but the complexity of endothelial keratoplasty procedures was also a significant barrier,” he said.

His team devised a method of injecting healthy CECs directly into the anterior chamber of the eye. To facilitate cell attachment to the posterior corneal surface, they formulated a solution including a rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitor.

“Thanks to Dr. Junji Hamuro, we realized that mature-differentiated CECs in vitro are the preferred choice for this procedure,” he added. After years of development and animal studies, this technique began treating human patients in 2013 and is now being commercially developed by Aurion Biotech.

Overcoming Resistance to Change

Despite proven effectiveness, new treatments often face skepticism.

Dr. Holland observed that some physicians are hesitant to adopt systemic immunosuppression due to fear of side effects. “Sometimes the biggest barrier to new ideas is resistance to change,” he said. Patients are sometimes advised to accept vision loss rather than undergo the Cincinnati Protocol.

To address this, Dr. Holland founded the Holland Foundation for Sight Restoration. The goal is to establish ocular surface stem cell transplantation centers across the United States. “We hope to provide resources to overcome logistical hurdles that I faced early on,” he stated.

Professor Kinoshita echoed the importance of perseverance in the face of doubt. “Even when an idea seems innovative, it takes years of development,” he reiterated. Their dedication resulted in a technique that has restored vision for many patients, demonstrating the impact of unwavering commitment.